A Dual Process Theory of Mindreading

Lecturer: Stephen A. Butterfill

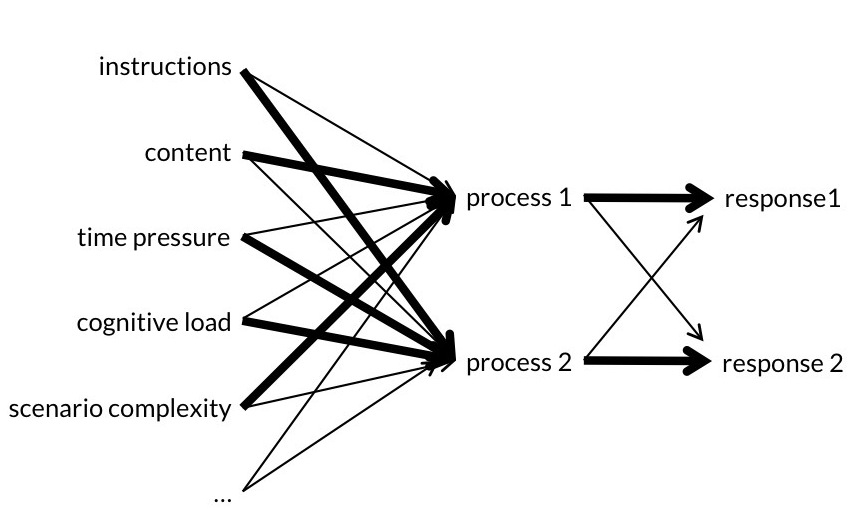

According to a (modest) dual process theory, there are two (or more) mindreading processes which are distinct in this sense: the conditions which influence whether they occur, and which outputs they generate, do not completely overlap.

If the slides are not working, or you prefer them full screen, please try this link.

Notes

This section is not covered in the lecture but may be useful if you are thinking further about this topic.

What is a dual-process theory? In general, a modest dual-process theory claims just this:

Two (or more) mindreading processes are distinct: the conditions which influence whether they occur, and which outputs they generate, do not completely overlap.

A key feature of this dual process theory is its theoretical modesty: it involves no a priori commitments concerning the particular characteristics of the processes. Identifying characteristics of the process is a matter of discovery. Further, their characteristics may vary across domains. The characteristics that distinguish processes involved in goal tracking may not entirely overlap with those that distinguish processes involved in segmenting physical objects and representing them as persisting, for example.

Figure: A modest dual-process theory claims only that two or more processes are distinct Source: homemade

Figure: A modest dual-process theory claims only that two or more processes are distinct Source: homemade

In the case of mindreading, we can elaborate a dual-process theory by starting with automaticity, as this is one of the most-studied features, and add a claim about signature limits which appears to be partially supported by the available evidence:

Dual Process Theory of Mindreading. Automatic and nonautomatic mindreading processes are independent in this sense: different conditions influence whether they occur and which ascriptions they generate (see Automatic Mindreading in Adults); and the automatic processes only rely on a minimal model of minds and actions (see Signature Limits).

A Developmental Theory

- Automatic and nonautomatic mindreading processes both occur from the first year of life onwards.

- The model of minds and actions underpinning automatic mindreading process does not significantly change over development.

- In the first three or four years of life, nonautomatic mindreading processes involve relatively crude models of minds and actions, models which do not enable belief tracking.

- What changes over development is typically just that the model underpinning nonautomatic mindreading becomes gradually more sophisticated and eventually comes to enable belief tracking.

Objections

Christensen and Michael argue that the dual process theory is less well supported overall than an alternative:

‘A cooperative multi-system architecture is better able to explain infant belief representation than a parallel architecture, and causal representation, schemas and models provide a more promising basis for flexible belief representation than does a rule-based approach of the kind described by Butterfill and Apperly’ (Christensen & Michael, 2016; see also Michael & Christensen, 2016; Michael, Christensen, & Overgaard, 2013).